NFA -> DFA with Subset Construction

Need to build a simulation of the NFA

Two key functions

move(si, a)is a set of states reachable from si by aε-closure(si)is the set of states reachable from si by ε

The algorithm (sketch):

- Start state derived from s0 of the NFA

- Take its

ε-closureS0 =ε-closure(s0) - For each state S, compute

move(S, a)for each a ∈ Σ, and take it’s ε-closure - Iterate until no more states are added

Sounds more complex that it is…

Example

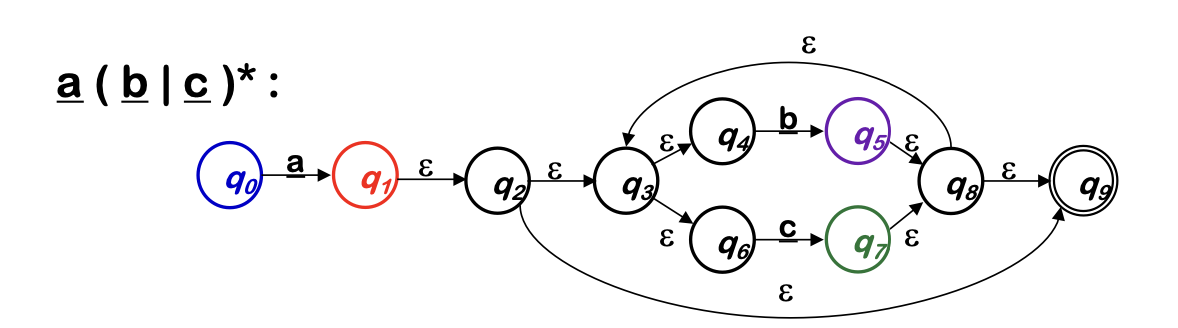

Applying the subset construction:

| DFA States | NFA States | a | b | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| s0 | {q0} | {q1, q2 q3, q9, q4, q6 } | none | none |

| s1 | {q1,q2,q3,q9,q4,q6} | none | {q5, q8, q3, q6, q4, q9} | {q7, q8, q9, q3, q4, q6} |

| s2 | {q5, q8, q9, q3, q4, q6 } | none | s2 | s3 |

| s3 | {q7, q8, q9, q3, q4, q6 } | none | s2 | s3 |

Note that any NFA state that contains q9 is an accepting state, since that is the final state in the NFA

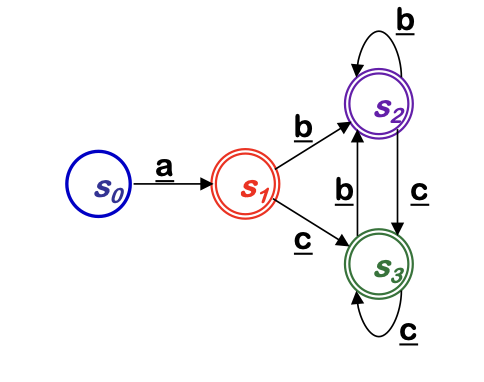

The result of subset construction is the following DFA

| δ | a | b | c |

|---|---|---|---|

| s0 | s1 | - | - |

| s1 | - | s2 | s3 |

| s2 | - | s2 | s3 |

| s3 | - | s2 | s3 |

- Ends up smaller than the NFA

- All transitions are deterministic

Automatic Scanner Construction

-

RE -> NFA (Thompson’s construction)

- Build an NFA for each term

- Combine them with ε moves

-

NFA -> DFA (subset construction)

- Build the simulation

-

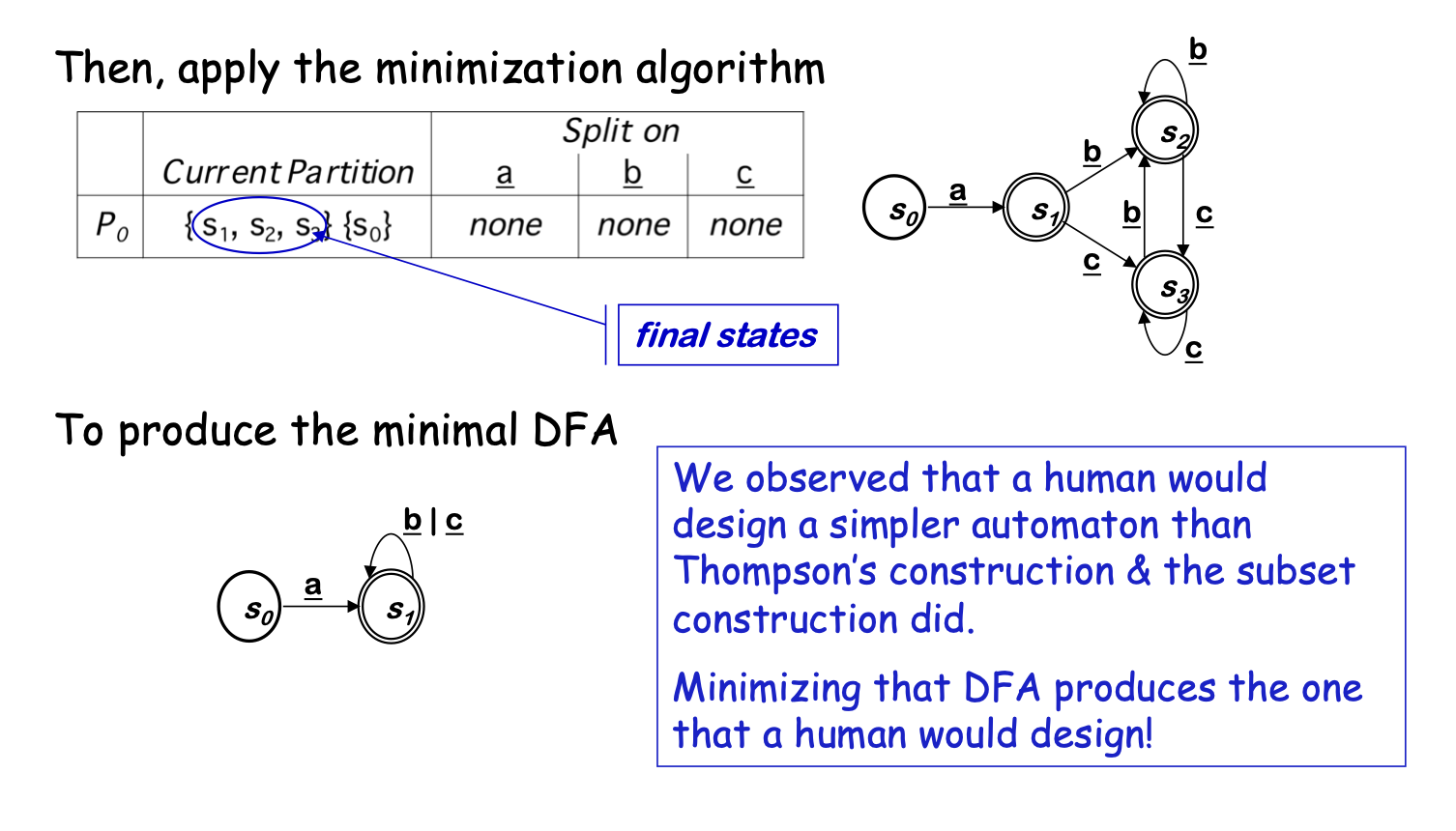

DFA -> Minimal DFA

- Hopcroft’s Algorithm

-

DFA -> RE (not really part of scanner construction)

- All pairs, all paths problem

- Union together paths from s0 to a final state

DFA Minimization

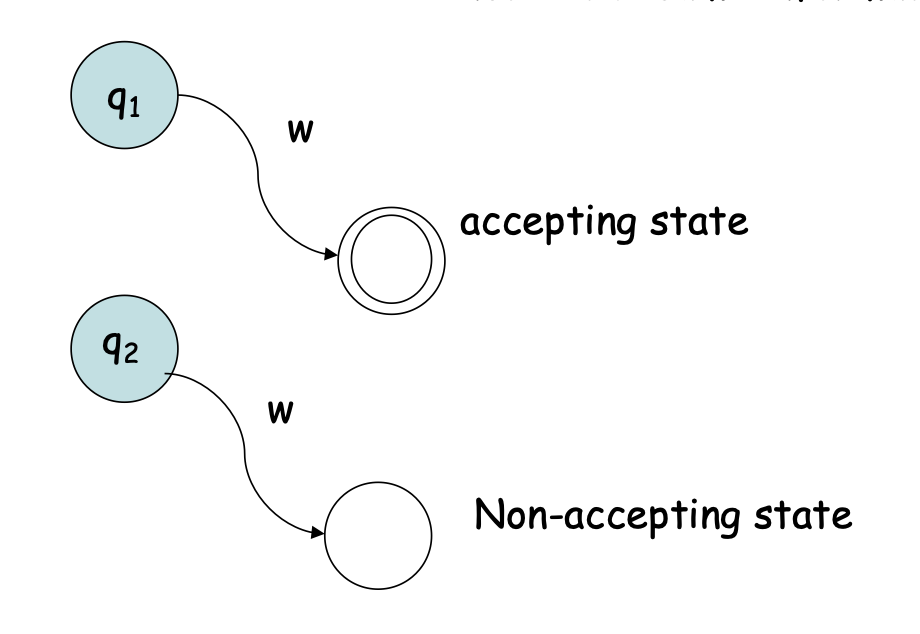

- How do we know whether two states encode the same information?

- Here, q1 and q2 are not equivalent. “w” is a witness that they are not equivalent

Intuition: Two states are equivalent if for all sequences of input symbols “w” they both lead to an accepting state, or both end up in a non-accepting state.

Big Picture

- Discover sets of equivalent states

- Represent each such set with just one state

Two states are equivalent if and only if:

- ∀ a ∈ Σ, transitions on a lead to equivalent states (DFA)

- if a-transitions to different sets => two states must be in different sets, i.e., cannot be equivalent

A partition P of S

- Each state s ∈ S is in exactly one set pi ∈ P

- The algorithm iteratively partitions the DFA’s states

Details of the algorithm

- Group states into maximal size sets, optimistically

- Iteratively subdivide those sets, as needed

- States that remain grouped together are equivalent

Initial partition, P0, has two sets: {F} & {Q-F}

Splitting a set (“partitioning a set s by a”)

- Assume qa & qb ∈ s, and δ(qa, a) = qx & δ(qb, a) = qy

- If qx & qy are not in the same set, i.e., are considered equivalent, then s must be split

- qa has transition on a, qb does not => a splits s

Back to our DFA Minimization example

Limits of Regular Languages

Advantages of Regular Expressions

- Simple & powerful notation for specifying patterns

- Automatic construction of fast recognizers

- Many kinds of syntax can be specified with REs

Example - an expression grammar

Term -> [a-zA-Z]([a-zA-Z] | [0-9])*

Op -> + | - | * | /

Expr -> ( Term Op )* TermOf course, this would generate a DFA

If REs are so useful… Why not use them for everything?

Not all languages are regular

RL’s ⊂ CFL’s ⊂ CSL’s

You cannot construct DFAs to recognize these languages

- L = {p^k q^k}

- L = {wcw^r | w ∈ Σ*}

Neither of these is a regular language But, this is a little subtle. You can construct DFA’s for

- Strings with alternating 0’s and 1’s

- Strings with an even number of 0’s and 1’s

- Strings of bit patterns that represent binary numbers which are divisible by 5 (homework)

What can be so hard?

Poor language design can complicate scanning

- Reserved words are important

if then then then - else; else else = then(PL/I)

- Insignificant blanks (Fortran & Algol68)

do 10 i = 1,25do 10 i = 1.25

- String constants with special characters (C, C++, Java)

- newline, tab, quote, comment delimiters

- Limited identifier “length” (Fortran 66 & PL/I)