Lecture 13 - More Parsing

Top-down parsers

LL(1), recursive descent

- Input: read left to right

- Construct leftmost derivation

- 1 input symbol look ahead

Example

Grammar S -> % S % | & S & | $

Our language can be described mathematically as: {w $ w^R | w ∈ (%, &)^*}

Is this LL(1)?

Yes! Because as you push the left most derivation through, you only need to look ahead one token at a time, and you end up with a deterministic parse tree.

The grammar S -> % S % | % & S % | $ is NOT LL(1), but rather LL(2).

Formally defining LL(1)

A -> 𝝰 | 𝛃 s.t. First(𝝰) ∩ First(𝛃) = ∅

But, how do we compute the First sets?

Left Recursion

Remember the expression grammar?

Goal -> Expr

Expr -> Expr + Term

| Expr - Term

| Term

Term -> Term * Factor

| Term / Factor

| Factor

Factor -> number

| idTop-down parsers cannot handle left-recursive grammars

Formally, A grammar is left recursive if ∃ A ∈ NT such that ∃ a derivation A =>^+ A𝝰, for some string 𝝰 ∈ (NT ∪ T)^+

Our expression grammar is left recursive

- This can lead to non-termination in a top-down parser

- For a top-down parser, any recursion must be right recursion

- We would like to convert the left recursion to right recursion

Non-termination is a bad property in any part of a compiler

Eliminating Left Recursion

To remove left recursion, we can transform the grammar

Consider a grammar fragment of the form

Fee -> Fee 𝝰

| 𝝱where neither 𝝰 nor 𝝱 start with Fee

We can rewrite this as

Fee -> 𝝱 Fie

Fie -> 𝝰 Fie

| 𝝴where Fie is a new non-terminal

This accepts the same language, but uses only right recursion

Roadmap (Where are we?)

We set out to study parsing

- Specifying syntax

- Context free grammars

- Ambiguity

- Top-down parsers

- Algorithm & its problem with left recursion

- Left-recursion removal

- Left factoring (will discuss later)

- Predictive top-down parsing

- The LL(1) condition

- Table-driven LL(1) parsers

- Recursive descent parsers

- Syntax directed translation (example)

Picking the “Right” production

If it picks the wrong production, a top-down parser may backtrack. Alternative is to look ahead in input & use context to pick correctly

How much look ahead is needed?

- In general, an arbitrarily large amount

- Use the Cocke-Younger, Kasami algorithm or Earley’s algorithm

Fortunately

- Large subclasses of CFGs can be parsed with limited look ahead

- Most programming language constructs fall in those subclasses

Among the interesting subclasses are LL(1) and LR(1) grammars

Predictive Parsing

Basic idea Given A -> 𝝰 | 𝝱, the parser should be able to choose between 𝝰 and 𝝱

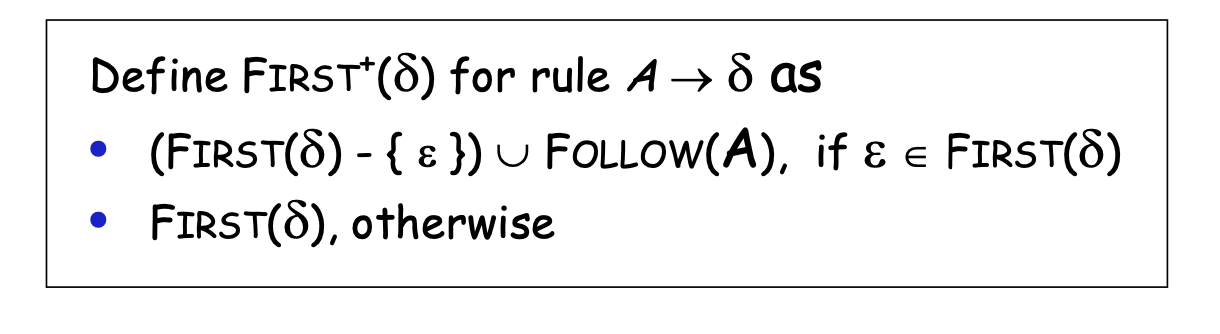

FIRST Sets

- For some rhs 𝝰 ∈ G, define FIRST(𝝰) as the set of tokens that appear as the first symbol in some string that derives from 𝝰

- That is, a ∈ FIRST(𝝰) iff a =>^* a𝝲, for some 𝝲

The LL(1) property If A -> 𝝰 and A -> 𝝱 both appear in the grammar, we would like FIRST(𝝰) ∩ FIRST(𝝱) = ∅

- Note: This is almost correct, but not quite!

This would allow the parser to make a correct choice with a look ahead of exactly one symbol!

The FIRST Set - 1 Symbol Look ahead

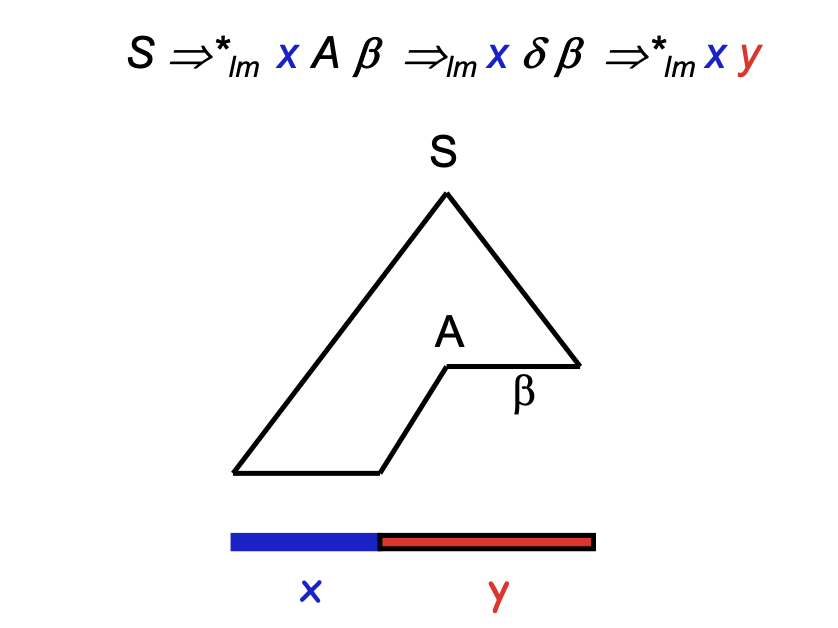

The FOLLOW Set - 1 Symbol

For a non-terminal A, define FOLLOW(A) as

FOLLOW(A) := the set of terminals that can appear immediately to the right of A in some sentential form

Thus, a non-terminal’s FOLLOW set specifies the tokens that can legally appear after it; a terminal has no FOLLOW set

FOLLOW(A) = { a ∈ (T ∪ {eof}) | S eof =>^* 𝝰 A a 𝝲 }

To build FOLLOW(X) for all non-terminal X

- Place eof in FOLLOW(<goal>)

- Iterate until no more terminals or eof can be added to any FOLLOW(X)

- If A -> 𝝰B𝝱 then put {FIRST(𝝱) - 𝝴} in FOLLOW(B)

- If A -> 𝝰B then put FOLLOW(A) in FOLLOW(B)

- If A -> 𝝰B𝝱 and 𝝴 ∈ FIRST(𝝱) then put FOLLOW(A) in FOLLOW(B)

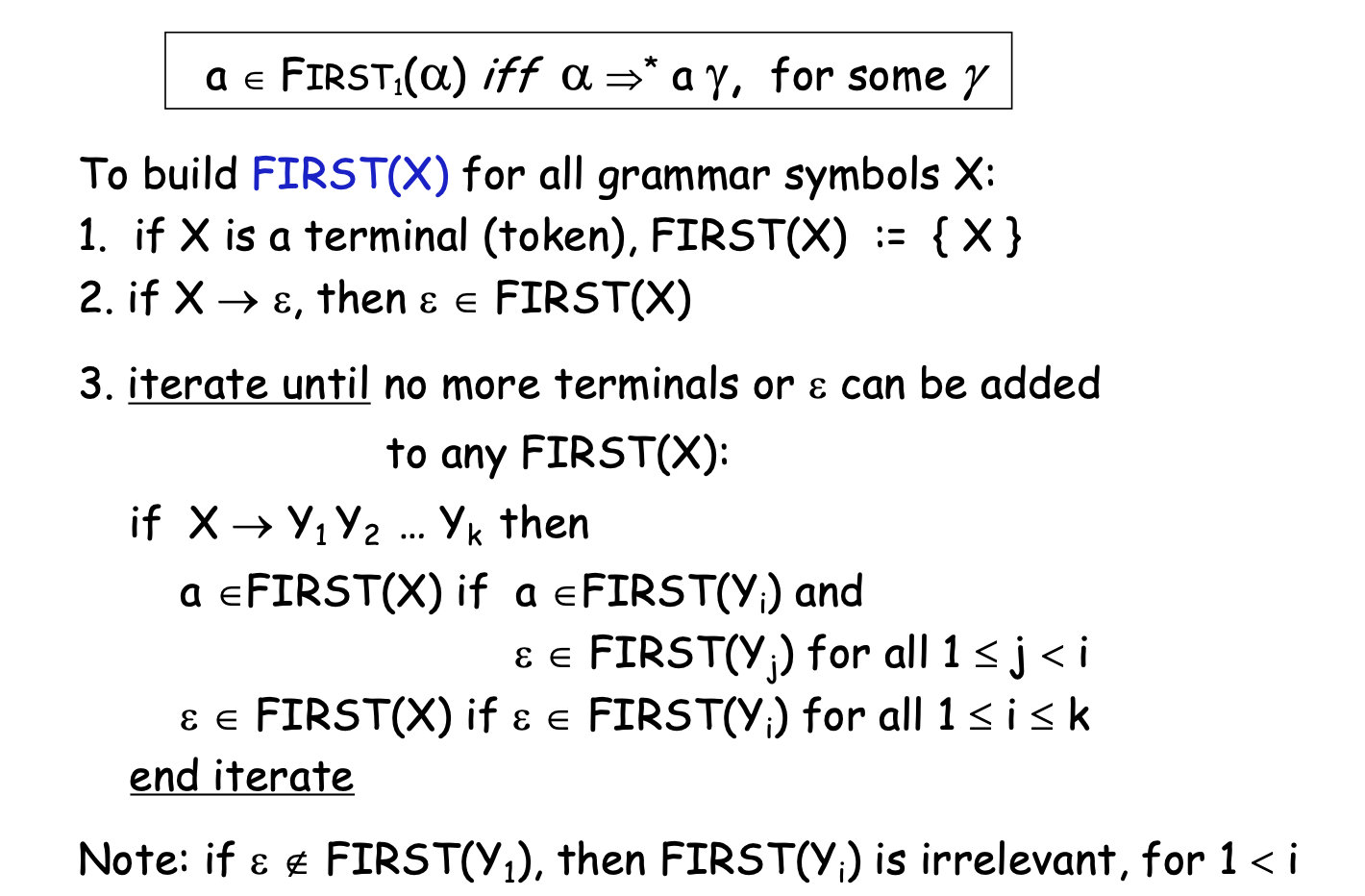

If A -> 𝝰 and A -> 𝝱 and 𝝴 ∈ FIRST(𝝰), then we need to ensure that FIRST(𝝱) is disjoint from FOLLOW(A), too