Lecture 4

Instruction Scheduling (part 3)

Code:

a: loadAI r0,@w => r1

b: add r1,r1 => r1

c: loadAI r0,@x => r2

d: mult r1,r2 => r1

e: loadAI r0,@y => r3

f: mult r1,r3 => r1

g: loadAI r0,@z => r2

h: mult r1,r2 => r1

i: storeAI r1 => r0,@wNote: store can cause aliasing issue, so for our projects we will always use storeAI

Local (forward) List Scheduling

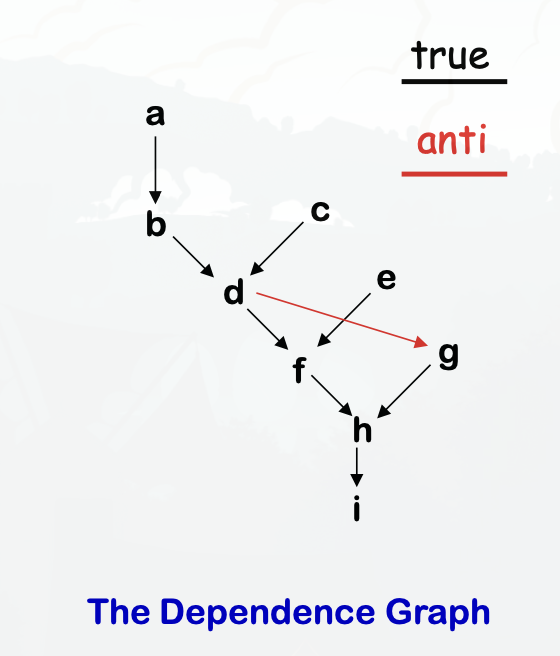

Step 1. Build the dependence graph

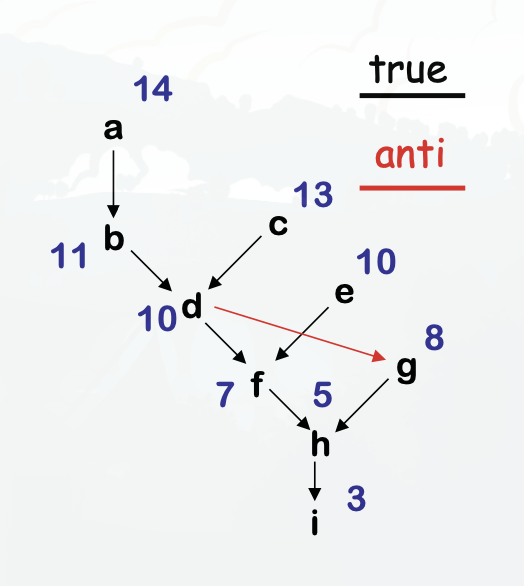

Step 2. Determine priorities

- Find the longest latency-weighted path

Example

- You can schedule the instructions efficiently by prioritizing scheduling instructions in the critical path

- Instructions that can be queued are stored in the Ready Set

- Instructions that are currently queued are in the Active Set

- You then traverse the graph, using the sets, and can generate more efficient, faster code.

Example:

| Cycle | Ready Set | Active Set | What happened |

|---|---|---|---|

| a, c, e | Move a to active set | ||

| 0 | c,e | a | |

| 1 | e | a, c | Move c to active set |

| 2 | a, c, e | Move e to active set | |

| 3 | b, c, e | Remove a from active set since it has finished, and add b to the ready set since it depended on a. Move b to active set | |

| 4 | d, e | Remove b and c from active set since they have finished, and add d to the ready set since it depended on b. Move d to the active set | |

| 5 | d | Remove e from the active set since it has finished. We can’t add f yet since it’s still waiting on d | |

| 6 | f | g | Remove d form the active set, and add f and g to the ready set. We schedule g first because it has a higher latency-weighted path. |

| 7 | g, f | Move f to the active set | |

| 8 | g, f | Nothing we can do here | |

| 9 | h | Remove g and f from the active set since they have both finished. Add h to the ready set, and move it to the active set. | |

| 10 | h | Nothing to do, waiting on h to finish | |

| 11 | Remove h from the active set, and add i to the ready set. Move i to the active set | ||

| 12 | Nothing to do, waiting on i to finish |

Generated Code

0: a: loadAI r0,@w => r1

1: c: loadAI r0,@x => r2

2: e: loadAI r0,@y => r3

3: b: add r1,r1 => r1

4: d: mult r1,r2 => r1

5:

6: g: loadAI r0,@z => r2

7: f: mult r1,r3 => r1

8:

9: h: mult r1,r2 => r1

10:

11: i: storeAI r1 => r0,@w

12:By using the dependency graph and List scheduling, we turned 20 cycles into 14!

Algorithm

Cycle <- 0

Ready <- leaves of P

Active <- empty

while (Ready ∪ Active != empty)

if (Ready != empty) then

remove an op from Ready

S(op) <- Cycle

Active <- Active ∪ op

Cycle <- Cycle + 1

for each op ∈ Active

if (S(op) + delay(op) <= Cycle) then

remove op from Active

for each successor s of op in P

if (s is ready) then

Ready <- Ready ∪ sFormalisms

- A correct schedule maps each n in N into a non-negative integer representing its cycle number such that

- S(n) >= 0, for all n in N (obviously)

- If (n1, n2) in E, S(n1) + delay(n1) <= S(n2)

- For each type t, there are no more operations of type t in any cycle than the target machine can issue

The length of a schedule S, denoted L(S), is:

- L(S) = max(n in N)(S(n) + delay(n))

The goal is to find the shortest possible correct schedule. S is time-optimal if L(S) <= L(S1), for all other schedules S1.

Note: We are trying to minimize execution time here.

What’s so difficult?

Critical points

- All operands must be available

- Multiple operations can be ready

- Operands have multiple predecessors Together, these issues make scheduling hard (NP-Complete)

Local scheduling is the simple case

- Restricted to straight-line code (single basic block)

- Consistent and predictable latencies